Opioid prescriptions decline but deaths from overdose rise

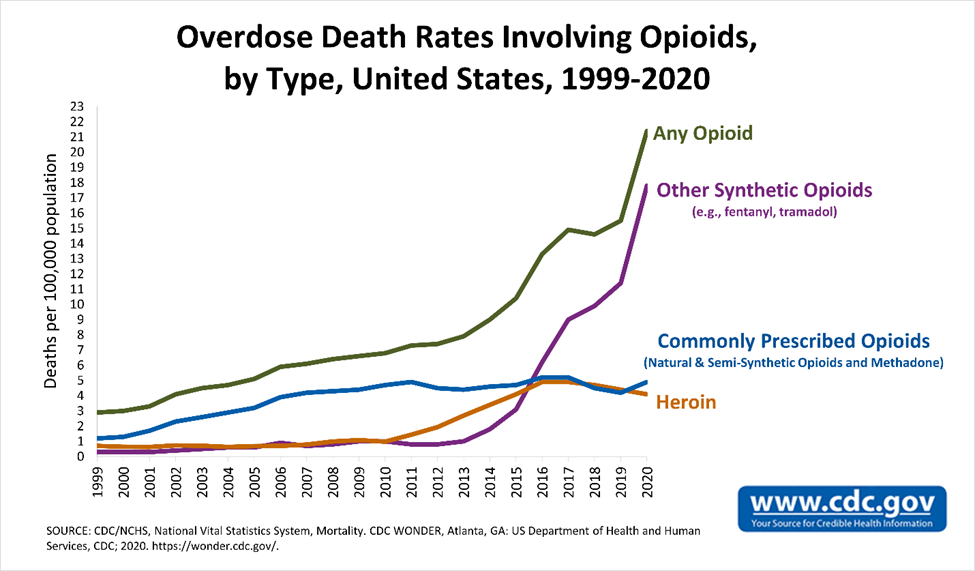

LEXINGTON The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported more than 100,000 people died of drug overdoses in the U.S. during the 12-month period ending April 2021. That’s a new record high! Overdose deaths jumped nearly 29% from the same period a year earlier and nearly doubled over the past five years. Opioids continue to be the driving cause of the deaths, and synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl and its analogs, caused about 64% of all drug overdose deaths in that same time period.

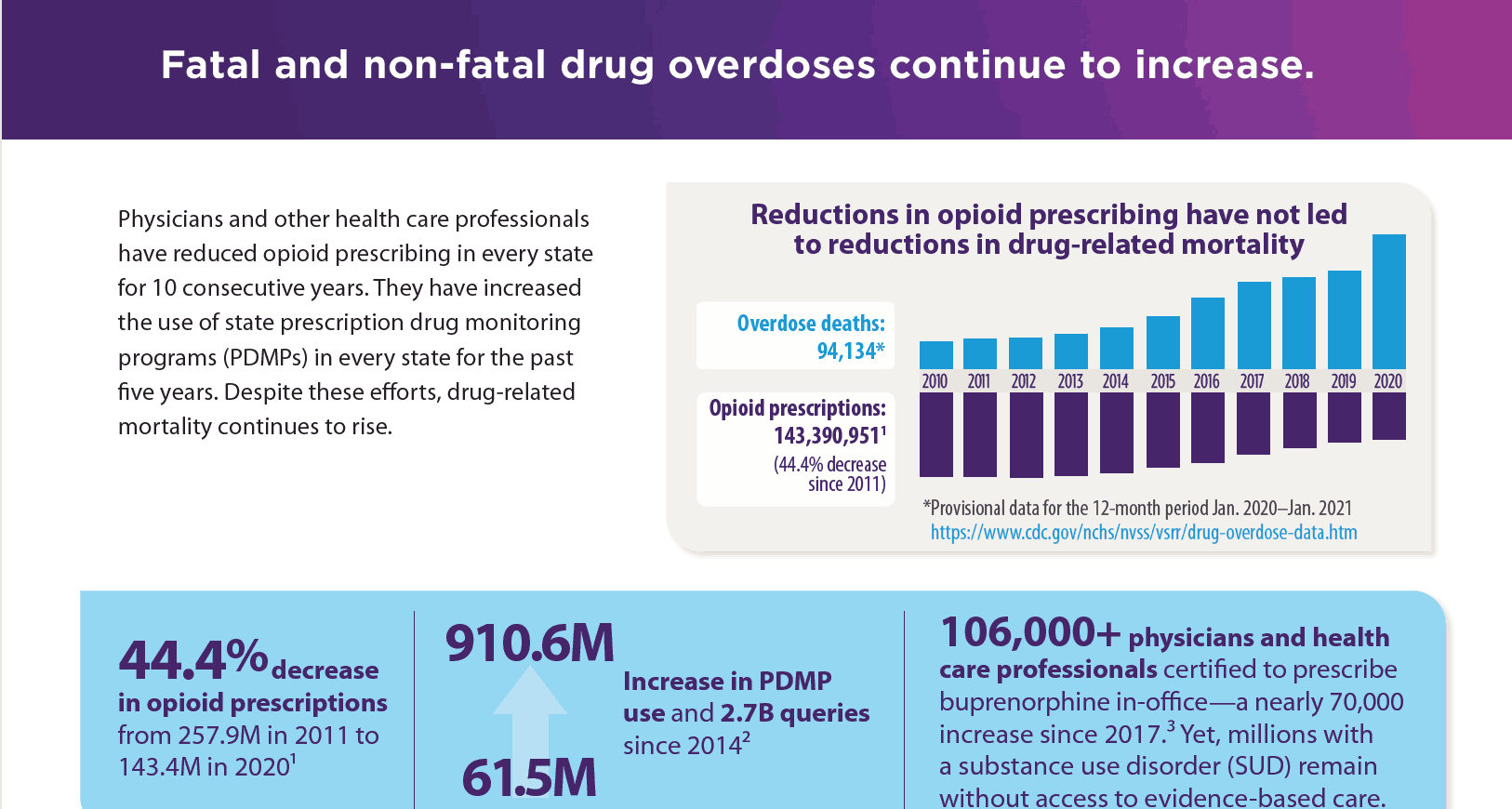

Although we have achieved tangible victories in our efforts to combat the opioid epidemic, it appears that we are losing the war. Opioid prescriptions have dramatically declined in every state for the last 10 consecutive years. Participation in state prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) has increased in every state for the past five years. Harm reduction and other community-based efforts distributed more than 3.7 million doses of naloxone between 2017-2020. Despite these measurable accomplishments, the nation’s overdose death rates related to opioids continue to worsen. Certainly, the physical isolation and financial insecurity caused by the COVID19 pandemic exacerbated the situation, but the rising trend in overdose deaths related to opioids predated the pandemic. What are we missing? What unintended consequences did we cause as the result of the implementation of these strategies to combat the opioid epidemic?

Many of us are familiar with the general story of how the recent opioid epidemic began. Doctors Hershel Jick and Jane Porter wrote a one paragraph editorial in 1980 to The New England Journal of Medicine reporting that after an analysis of 12,000 hospitalized patients who were given opioid analgesics, the risk of addiction was less than 1%. Companies like Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of Oxycontin, aggressively promoted the idea that opioids were not addictive. Patient advocates and pain specialists convinced the medical community to raise its awareness that doctors were unresponsive to patients suffering from unnecessary pain. Federal regulators, doctors, and everyone persuaded by pharmaceutical companies demanded the assessment of pain as the “fifth vital sign.” The liberal prescription of opioid analgesics began, and the opioid epidemic followed shortly thereafter.

Once the opioid epidemic became apparent, the medical community reassessed the safety of opioids and discovered that they were not safe. In fact, opioids were tremendously addictive. We also realized that the liberal prescribing of opioids created an excessive supply. Many patients with addiction confided that their initial exposure to opioids was from someone else’s leftover prescription. As a result, the medical, regulatory, and legislative communities reacted with a 180-degree shift to essentially no opioid prescribing. There has been a steady decline in prescription opioids of about 44.4% from 257.9 million prescriptions in 2011 to 143.4 million in 2020. Figure 2 shows that, despite our efforts to decrease the amount of prescription opioids, the mortality associated with opioid overdoses continues to rise.

An immediate thought should be, if we decrease the supply of prescription opioids, what are these patients with addiction going to do? How are they going to resolve their withdrawal symptoms? Certainly, these patients can go to their local doctor for treatment. However, it’s probably much easier to simply find heroin, and Figure 1 clearly shows that in 2011, many patients did just that. And as law enforcement cracked down on the heroin supply, we saw the rise in synthetic opioids — fentanyl and its many new and creative analogs.

There is another more concerning side effect of decreasing prescription opioids. When we adopted the 180-degree shift in our stance toward opioids, there were many patients with legitimate pain whose voices were essentially ignored. Patients were simply informed that there was not an indication for opioid analgesics with the rare exception of surgery or trauma. So how did we get from, “We must assess a patient’s pain and avoid unnecessary suffering,” to “Opioids will not help your pain”? In a very lengthy letter on June 16, 2020 to CDC doctor Deborah Dowell, MD, MPH, the AMA’s James Madara, MD, cites the data in Figure 2 and states, “We can no longer afford to view increasing drug-related mortality through a prescription opioid-myopic lens.” He continues, “The nation’s opioid epidemic has never been just about prescription opioids, and we encourage CDC to take a broader view of how to help ensure patients have access to evidence-based comprehensive care…” Later in the letter, Madara writes, “The CDC Guideline has harmed patients.” Patients suffering from pain view themselves as “collateral damage” from regulatory and legislative efforts to restrict opioid prescribing. The CDC has acknowledged its Guideline’s negative effect on patients with legitimate pain.

In addition to the dramatic change in how we view patients with pain, the regulatory restrictions have completely changed doctors’ practices. Doctors are very fearful of prescribing any opioids. As a result, patients are either abandoned, involuntarily tapered off their opioids, or referred to a pain management specialist who will face the same dilemma. A recent study (Sedney et al., 2022) interviewed 20 physicians in West Virginia regarding opioid prescribing and reported four general responses:

1) fear of disciplinary action, 2) exacerbation of opioid prescribing fear due to restrictive legislation, 3) care shifts and treatment gaps, and 4) conversion to illicit substances. Physicians feared that taking on patients who legitimately required opioid pain medications would jeopardize their career. Interestingly, several physicians confided that some of the patients who were seen for addiction related that their heroin and/or fentanyl addiction was directly related to being abandoned by their regular doctors. Similar to the disappointment seen with rising overdose deaths despite decreases in prescription opioids, participation in PDMPs has not correlated with a decline in overdose deaths. The use of PDMPs has grown from 61.5 million in 2014 to 910.6 million in 2020 with over 2.7 billion queries. Many legislative and regulatory experts reported that the intent of PDMPs was to reduce the prescription of controlled medications. The registry is simply another tool to combat the opioid epidemic, but alone, it is not sufficient to win the war on opioid overdose deaths.

I certainly do not have the solutions to ending the opioid epidemic. However, I am very happy to see that many of our academic colleagues are examining supply-demand mismatches. Simply removing the supply of prescription medications and/or illicit drugs will not cause a decrease in demand. As we have seen, patients with addiction will seek their medications elsewhere and the elsewhere may often not be very safe. We saw this with the shift to heroin when prescription opioids were forcibly removed. And when we aggressively eliminated heroin, fentanyl emerged. Thus, increasing access to proper evidence-based treatment is critical to ensure that the patients’ demands are met in a safe and controlled environment. More importantly, the addicted patients are often impulsive and volatile. When they are ready for treatment, we need to quickly meet their needs then. Any delays in treatment such as prior authorizations may result in missed opportunities.

I embrace the AMA’s effort to combat the opioid epidemic and support their initiatives: Remove barriers to evidence-based care for patients with substance use disorder (SUD) such as prior authorization. Remove barriers to medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) for SUD and co-occurring mental illness in jails and prisons. Protect families by focusing on increasing access to evidence-based care instead of punishment or threat of separation for persons who are pregnant, peripartum, postpartum and parenting. Support patients with pain by rescinding arbitrary laws and policies focused on restricting access to multidisciplinary, multimodal pain care.

Tuyen Tran, MD, emigrated from South Vietnam after the war. He completed his undergraduate in biology/ chemistry and medical school at the University of Missouri – Kansas City. His is currently boarded in internal medicine and addiction medicine and current president of Kentucky Society of Addiction Medicine. He is a past president and executive board chairman of the Lexington Medical Society.

REFERENCES

- Robinson, Amber, Aleta Christensen, and Sarah Bacon. “From the CDC: The Prevention for States Program: Preventing Opioid Overdose through Evidence-Based Intervention and Innovation.” Journal of Safety Research 68 (2019): 231–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2018.10.011.

- Sedney, Cara L., Treah Haggerty, Patricia Dekeseredy, Divine Nwafor, Martina Angela Caretta, Henry H. Brownstein, and Robin A. Pollini. 2022. “‘The DEA Would Come in and Destroy You’: A Qualitative Study of Fear and Unintended Consequences among Opioid Prescribers in WV.” Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 17 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-022-00447-5

- IQVIA Institute Custom Xponent Opioid Dataset, Specialty View. For more information, IQVIA Institute Prescription Opioid Trends in the United States (December 16, 2020). Available at https://www.iqvia.com/en/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/ prescription-opioid-trends-in-the-united-states.